Brasilia: living within modernist standards

Brasilia: living within modernist standards

by:

Marcio N. de Oliveira

(originally written in 98 for Maquis, my old Geocities homepage)

Introduction:

Latin American countries have always pursued a sense of urban utopia. Nowhere else have modernistic urban theories, above all Le Corbusier's, controlled the minds of practicing architects and urban designers as much as in Latin America and specially Brazil. Brasilia was designed according to them and quite clearly exemplifies the shortcoming of such urban theories. Erected in record setting time of three years (1957-60), the city was planned in relation to Brazil's need to conquer physically, culturally and economically its own continent sized countryside. With this short essay I intend to show one view, the one of a natural Brasiliense, born and raised in Brasilia, living the daily life within modernist standards.

Superquadras and Apartment Blocks:

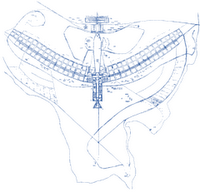

In Brasilia's urban landscape the central city was made up of two dense residential cores (south and north wings) .Each wing is divided into nine bands, from 100 to 900. The band's number indicates its position to the east or the west of the axial speedway that crosses it. The bands 100 to 400 contains the superquadras, two rows in each side of the speedway.

At a functional rather than symbolic level, the superquadra was conceived of as a self-sufficient residential unit with its own facilities and linked to three of its neighbors by other, shared facilities. As an autonomous unit, each in principle offers its residents four kinds of basic services such as commerce, child care, education, etc.

An individual superquadra contains from 8 to 11 apartment blocks distributed along an area of approximately 240 by 240 meters according to a standard layout. Although they may look rather boring repetitious on paper, the urban spaces are in fact more varied than one would assume. The open green spaces makes up to 60% of the total area. Each quadra (as locals call it) is designed as a kind of park, free of traffic, surrounded by a relatively wide tree ring and containing sport and recreational facilities for the social use of residents.

In Brasilia there are about 25 square meters of green space per resident, a measure considered ideal by UNESCO standards (by contrast, there are 4.5 meters of green area per inhabitant in metropolitan São Paulo). The impression of a passer by, driving or walking, is that the buildings are involved in a ring of trees, some of them totally covered by the luxurious specimens common to the cerrado climate. The resulting scenario results indeed interesting, given the contrast of the green mass against the glossy white of marble facades. This impression diverges with the image that most people have of Brasilia - that of a dry, empty space - that derives mostly from pictures taken on early stages of occupation.

In terms of livability most inhabitants evaluate the superquadra based on their previous experience within the residential organization of other Brazilian cities, eventually comparing its daily life with that of a traditional bairro.1 In the case of the new brasiliense generation, this comparison also exists, but in the opposite way.

The Apartment Unit:

The typical apartment blocks of the quadra in Brasilia are built on a rectangular projection, all uniformly of six stories not counting the pilotis, which is meant to allow free circulation and visualization of the surroundings between the blocks. In some areas, as in the case of bands 400, the blocks are all three stories high, some without but most withpilotis.

The design of the dwellings, unlike the rectangular projection, have changed considerably in its character. New concepts and ideas are incorporated each year, the majority on buildings located at the north wing side, in which a few pockets of land are still available for development.

When comparing houses and apartments, as when comparing bairros and superquadras, an important component of this residential ideal emerges - that of the family's social life within the domestic sphere. Based on the organization of the middle-class house, the family apartment in Brasilia is divided in three functionally independent zones: the social area, the intimate area, and the service area. As a reflection of the social structure of the middle-class Brazilian household, the plan is divided between masters, who occupy the social and intimate areas, and servants who work and live in the service area. This division is a norm of middle-class life, for it is practice for even modest middle-income families to employ cheap domestic labor to cook, clean, wash and baby-sit.

In a typical apartment, the social area consists of a visiting room, a dining room, a copa, and a balcony. In most households the living and dining rooms are rarely used formal spaces, the former reserved for the reception of visitors and, in some cases, for the main meal when the head of the family is home from work.

In old traditional houses the varanda was the main gathering place, the heart of the informal social life of the family. In Brasilia's apartments this place of daily, informal gathering, is the copa2. Thus the copa is a multipurpose room associated with the kitchen. It may be described as the most democratic space of the apartment, equally accessible to every member. It is the space in which the household superimposes the relations of leisure and work, of socializing and service.

In the rest of the apartment, the three zones are kept entirely separate. The principle of separation becomes most highly elaborated in upper-class dwellings, thus it is not only a matter of separating functions but, more important, of separating classes. I will not discuss here, however, the merits or demerits of this separation, which relates to traditions and social culture.

The service area of the apartment consists of the kitchen, the maid's bath and bedroom, and the laundry facilities. Usually bordered by two corridors, the service on one side and the that of the intimate zone on the other side, the service area is effectively isolated from other areas of the apartment. direct access to the kitchen from the dining room is rarely tolerated.

Comments:

The Brazilian modernist utopia has been extensively discussed in the architectural world since its origins in late 50s. However the majority of its recent reviewers tend to overlook the experience of the first generation of brasilienses, the ones that shaped the city's development and sometimes not only rejected these views but moreover countered them with opposing interpretations. Most brasiliense families manifest their rejections of Brasilia's utopian design by reasserting familiar values, conceptions, and conventions of urban life, often based on their own experience. The character of a city is built by tradition, which Brasilia, at 49, undoubtedly still lacks.

References:

- Costa, Lucio. Relatorio do Plano Piloto de Brasilia, 1990.

- Ludwig, Armin K. Brasilia's First Decade: A Study of its Urban Morphology and Urban Support Systems, 1980.

- Holston, James.The Modernist City: An Anthropological Critique of Brasilia. PhD Thesis,1989.

- Bullrich, Francisco. New Directions in Latin American Architecture. 1969.

- Mindlin, Henrique E. Modern Architecture in Brazil. 1956.

- Benevolo, Leonardo. Historia da Arquitetura Moderna. 1989.

Comentários

Postar um comentário