Pedestrian System at Brasilia's South Wing - A Critical Essay

Brasilia est peut-être la seule ville où une voie express soit l`artère principale de la zone résidentielle: c'est l'expression parfait de l'ère de l'auto."

- Introduction

- The Street Redefined

- The South Wing's Axial-Expressway

- The Underground Passageways

- Concluding Remarks

- References

Contents:

1. Introduction

Brasilia is almost 50 years old. Erected in record setting time of three years (1957-60), the city was planned in relation to Brazil's need to conquer physically, culturally and economically its own continent sized countryside. The young Brazilian capital is undoubtedly the most clear example of the ideals of `modernization' relentlessly pursued by Latin American countries during the first part of this century. This utopian city, though, was built to be more than merely the symbol of the so called "modern age". Rather, Brasilia realized one of the modern architecture's fundamental planning objectives: to redefine the urban function of traffic, therefore completely changing the relationship between pedestrians, cars and the street. With this short essay I intend to show some of the characteristics of Brasilia's layout and its effects on the behavior of its users, with particular attention to the south section of the residential-highway axis and its pedestrian underground passing system.

2. The Street Redefined

In Brasilia's urban landscape the central city, or plano piloto, was made up of two distinct residential cores, defined as the south and north wings. Each `wing' is divided into nine bands, numbered from 100 to 900. The band number indicates its position to the east or the west of the axial speedway. The bands 100 to 400 contains thesuperquadras, which constitute the heart of the residential area, housing about seventy percent of the total population of the plano. There are two rows of superquadras in each side of the speedway, or eixo rodoviário. The model that Lucio Costa developed for the quadras embodies fundamental modernist ideas of autonomy and community organization. Each is designed as an autonomous unit, in park-like setting, free of traffic, surrounded by a relatively wide tree ring and containing sport and recreational facilities for the social use of the residents. When comparing Brasilia's quadras with the traditional Brazilian neighborhood arrangement, an important component of this residential ideal emerges: that of the relationship between residents and the street. The discovery that Brasilia is a city without street corners produces a sense of disorientation in those who experience it for the first time. The fact that most streets lack intersections, along with the use of an unique address system, contribute to the creation of an entirely new urban behavior, which means that both pedestrians and drivers must learn to negotiate their urban locomotion in an completely `different' way. Therefore the `street life' acquire a completely new dimension. In a larger sense, Brasilia's street patterns may show that the `motorized citizen' had at last his influence and power recognized in a wider urban context.

Although the plane-shaped pilot plan clearly incorporated the principle of separation of motorized and pedestrian traffic through the use of "...free principles of highway engineering applied to the technique of urban planning.", Costa felt that such a system "...should not be taken to unnatural extremes, since it must not be forgotten that the car, today, is no longer Man's deadly enemy; it has been domesticated and is almost a member of the family. It only becomes `dehumanized' and reassumes its hostile, threatening attitude when it is reintegrated into the anonymous body of traffic. Then indeed Man and Motor must be kept apart, although one must never lose sight of the fact that, under proper conditions and for mutual convenience, co-existence is essential." (L. Costa, 1957)

In the traditional Brazilian city - the case of Rio, São Paulo and Belo Horizonte - the pedestrian normally strolls to the corner of any street, waits for the light and, with some degree of security, ventures to the other side. In Brasilia, where traffic circles and cloverleaf intersections replace the street corner and where there are therefore no crossings to distribute the right-of-way between pedestrians and vehicles, the rite of street crossing is distinctly more complex, and indeed more dangerous. The result is an imbalance of force which tends to reduce or even eliminate the figure of the pedestrian: everyone, or at least those who can afford, drives.

3. The South Axis-Expressway

The north-south axial urban expressway ( eixo rodoviário sul or simply eixão), clearly exemplifies the preoccupation with the private automobile. It was designed to be essentially an expressway, linking south and north sections in a `non-stop' fashion. It is the most clear reflection of the plan for the `automobile city' . It is with no surprise that some aerial photographs show a strong resemblance to Le Corbusier's 1922 proposals for "A city for 3 million". Also here one finds one of the main drawbacks of the plan: Although Lucio Costa carefully designed the interior of thesuperquadras for maximum pedestrian safety, it is virtually impossible for the pedestrian to traverse the city in the east-west direction without risking their lives. The poorer sectors of the population, those who depend on the use of public transportation, as well as bicycle or foot, experience it as a frightening and sometimes hostile environment. Frederico de Holanda analyses the question of pedestrian accessibility in Brasilia's central core, particularly for those using mass transport. He states that "the points of entry are often confusing or even apparently inaccessible causing the sense of dislocation to be heightened further".

4. The Underground Passageways

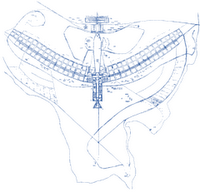

Like vehicles, pedestrians will always require proper measures to ensure their mobility, safety and pleasure. When analyzing the south wing's configuration and the availability of routes, pedestrian safety clearly is the most important preoccupation. As its main feature to prevent pedestrians from jaywalking across the dangerous expressway, Costa's plan provided underground passageways `strategically' located in each neighborhood's corner.

This solution soon proved to be ineffective in its goals. Although relatively comfortable and well ventilated, these passageways offered no other attractive feature that could draw the usual jaywalker's attention. Lack of safety was also a important concern for most of the inhabitants of the neighborhood and, despite the government attempts to introduce some sort of `neighborhood watch', it was still seen as unsafe for kids and the elderly. During the night, as in the case of most urban underpasses, these were places of youth gangs' gatherings and also frequently used as `alternative' restrooms to street beggars.

Recognizing the failure of this particular feature of the original plan, the municipal transit commission introduced some three years ago a package of safety measures, which included enhancing the driver's capacity of preventing accidents by adding more powerful street illumination systems and starting an informative campaign. High metal-structured fences, meticulously camouflaged with ornamental plants, were installed to prevent jaywalking along the identified `trouble areas'. Also special attention was given to the enforcement of the maximum speed limit (80 Km/h) through installation of photo-radars in key locations.

Although all these measures proved helpful in reducing the number of fatal accidents, the problem still continues, notably in those superquadras located closer to the city's CBD, where the traffic is particularly intense. Most people nevertheless prefer to risk their lives in the confrontation with the vehicular traffic than to use the filthy and unsafe passageways.

A new element currently being introduced into Brasilia's urban structure, an underground metro system, with stations strategically located along the south wing's axis ending at the center of the CBD, will undoubtedly add another dimension to the situation. It has been seen as a potential solution for the problem of pedestrian movement along the south wing's axis, and therefore very appealing to the minds of architects and urban planners, which are already proposing different ways to interconnect existing pedestrian passageways with the new subway stations.

5. Concluding Remarks

Lucio Costa's utopian design for Brasilia has been one of the most discussed subjects in the architectural world since its implementation in the early sixties. Despite the fact that it has constantly been interpreted as a beaux-arts solution by some critics and observers, Brasilia is in fact an interesting concept for linear urban development. Costa's idea for the park-like traffic-free residential superblock, which provides some twenty-five square meters of green space per resident, is now been recognized as a very pleasant living environment.

However, despite all these intrinsic qualities, one of the areas where the planning concept fails is at the treatment that is given to the axial expressway and its relationship to the residential areas that surround it. The solution of underpasses has proven to be inadequate and insufficient in itself, thus affecting both pedestrians and drivers in their freedom of movement.

Although the process of construction of the metro system is being continuously slowed down for economic and political reasons, it will be indeed interesting to observe how the pedestrians will respond to this addition to the city's structure after its implementation is consolidated.

6. References

- Costa, Lucio. Relatorio do Plano Piloto de Brasilia. Brasilia,1990.

- Ludwig, Armin K. Brasilia's First Decade: A Study of its Urban Morphology and Urban Support Systems, 1980.

- Holston, James. The Modernist City: An Anthropological Critique of Brasilia. Chicago,1989.

- Gosling, David. Brasilia in Third World Planning Review, 1979, v.1 n. 1, pg. 41-56.

- Paviani, Aldo. Brasilia: A Metropole em Crise - Ensaios sobre urbanização (Brasilia: The Metropolis in Crisis: Essays on Urbanization). Brasil, 1988.

- Holanda, Frederico. Brasilia: A inversão das prioridades urbanísticas. (Brasilia: the inversion of urban priorities). Essay for the ANPUR - VI, Brasilia, 1995.

- Holanda, Frederico. O centro urbano de Brasilia. ( Brasilia's urban center), Dec. 1975.

- Elenson, Norma. Two Brazilian Capitals. London, 1973.

- Gorovitz, Matheus. Brasilia. in Werk, Bauen + Wohnen: 1993 June, n.6, p.12-21.

- Richards, Brian. Moving in Cities, 1973.

- Hill, Michael R. Walking, Crossing Streets and Choosing Pedestrian Routes. , 1984.

Comentários

Postar um comentário